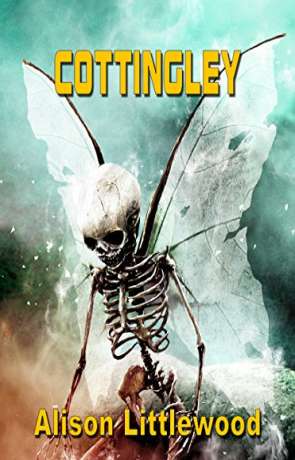

Cottingley

By Alison Littlewood

- Cottingley

-

Author: Alison Littlewood

-

Publisher: NewCon Press

- ISBN: 9781910935507

- Published: September 2017

- Pages: 82

- Format reviewed: Paperback

- Review date: 13/11/2017

- Language: English

- Age Range: N/A

My second review of the Newcon Press Novella series released in Autumn 2017. This is a set of four stories. The Wind by Jay Caselberg, Cottingley by Alison Littlewood, Body in the Woods by Sarah Lotz and Case of the Bedeviled Poet A Sherlock Holmes Enigma, by Simon Clark.

Cottingley by Alison Littlewood picks up a tangential thread from the famous fairy mystery surrounding photographs taken by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths that became known as the Cottingley Faeries. Littlewood’s work is a standalone story in Newcon Press’ second novella series, a collection of four fantasy books by four very different writers.

In Cottingley, Lawrence H. Fairclough writes a series of letters to a Mr Gardner, who is Edward Gardner, a member of the Theosophical Society of the 1920s and friend of Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle’s who made use of the Wright and Griffiths photographs in his 1922 work, The Coming of the Faeries. Conan-Doyle had learned of the existence of the photographs in 1920 and together with Gardner, sought to obtain proof that they were genuine.

Littlewood’s premise is that in 1921, her character (Fairclough) has become aware of this research and writes to Gardner and Conan-Doyle to have his experiences included in the publication. In his letters, he explains the circumstances around a series of encounters with faeries involving his daughter Charlotte, and granddaughter, Harriet. Fairclough’s letters are supposedly only revealed now, in 2017, having been ‘recently discovered’. This premise grants the book a series of layers and anchors it to existing texts and mythology, but it isn’t quite executed as well as it might be, with no mention of the discovery included in the story, only a reference to it on the back cover.

Littlewood chooses to include only Fairclough’s writings and not Gardner’s responses, but there is enough reconstitution in the letters to indicated what Gardner might be saying. This is deftly handled and never strays into the kind of awful one-sided telephone conversation where the narrator/speaker repeats what is being said to them.

Littlewood creates a voice for Fairclough through the letters which is both consistent and nostalgic. We get a sense of the period through his turn of phrase and choice of words. We also get a sense of the man’s capable nature, much in the way Edgar Allan Poe would make use of an intelligent but flawed narrator to draw the reader in. The gaps between letters are also important, noting the changes in his attitude at different times. Fairclough can be prideful and impulsive, but also contradictory and reflective as his temper cools. There is something different here in the purpose of letters. The very act of writing one, in modern society, is more effort than other ways of communicating, so the deliberate choice makes an individual consider their feelings. Fairclough does this, but still finds him regretting some of his missives as they are fuelled by his anger and frustration at not being believed, or his experiences being taken too lightly.

Littlewood also maintains the careful balance of myth and exposition/rationalisation. Fairclough wants to understand the world of Faeries, purportedly so too do Gardner and Conan-Doyle, but the story needs its characters to be thwarted and remain on the outside, otherwise it would lose its mysterious quality. The granddaughter, Harriet seems to come closest to this precious knowledge, but she also becomes distanced from Fairclough owing to her experiences. There are some clever touches here, referencing a wide selection of works on Faeries and their practices to give the story weight. Each reader will project their own reading experience into what happens. When considering Charlotte’s plight for example, I found myself thinking of Pohl Anderson’s, The Broken Sword.

The sequence of events builds towards a resolution which at first seems to be a restoration, but later turns into something altogether nastier. Again, Littlewood balances the narrative, ensuring the reader considers a plausible, non-magical explanation for the change in behaviour of Charlotte as well as Fairclough’s involved rationalisation. The power of a child’s perception, untainted by experience, is also well used as Harriet is both empowered and fragile throughout the tale. Ultimately it is both these qualities that lead Fairclough to his final decisions in the last letter. At this point, Littlewood’s artifice fails her slightly. The composed letters and varnished prose of Fairclough act as a distancing medium from the reader, so we do not feel the situation as deeply as we might if the circumstances were conveyed another way.

Cottingley is an excellently crafted novella, full of the aesthetic and mythical considerations of its period and context. If buried alongside the works of Conan-Doyle and the Wright/Griffiths photographs to be dug up by humanity in five hundred years’ time, a reader would be hard pressed to note the century between the original correspondences and Littlewood’s invented ones. The novella is in itself a successful changeling.

Written on 13th November 2017 by Allen Stroud .